Charles Bargue was a French artist and lithographer who created a series of “models” for training according to the academic style of art education. I have admired his work

for years, bought a copy of the Charles Bargue Drawing Course by Gerald M. Ackerman, and have fussed around in some effort to learn from it; I was not overly successful. However, this past fall, I determined to make an attempt to actually follow Bargue’s system.

A visit to the internet revealed several examples of artists actually doing the Bargue drawings, and I also found a video tape, The Bargue Drawing Companion, offered by the Academy of Realist Art in Toronto. Although rather pricey, I bought it. Fernando Freitas gives the lecture. I have watched it several times, gathered the tools he recommends (along with some others suggested elsewhere in my studies), and set up a modified training program.

I have also made extensive notes of the excellent material covered by Mr. Freitas, and have determined to study those notes every day as well. I am now launched on, at least, a two-year

study of the Charles Bargue drawing course.

Here is a drawing produced according to Freitas recommendations, applied to a Bargue plate from the Charles Bargue Drawing Course by Gerald M. Ackerman. This post is mostly for my own study, although I hope is will be of some interest to those who enjoy the study of art, and that it might also serve as an example of how determined effort can produce some level of success in all aspects of life.

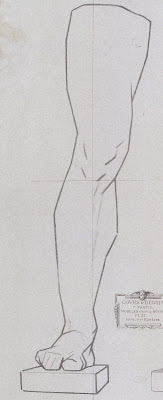

Plate I, 27. Leg of Germanicus, front view:

for years, bought a copy of the Charles Bargue Drawing Course by Gerald M. Ackerman, and have fussed around in some effort to learn from it; I was not overly successful. However, this past fall, I determined to make an attempt to actually follow Bargue’s system.

A visit to the internet revealed several examples of artists actually doing the Bargue drawings, and I also found a video tape, The Bargue Drawing Companion, offered by the Academy of Realist Art in Toronto. Although rather pricey, I bought it. Fernando Freitas gives the lecture. I have watched it several times, gathered the tools he recommends (along with some others suggested elsewhere in my studies), and set up a modified training program.

I have also made extensive notes of the excellent material covered by Mr. Freitas, and have determined to study those notes every day as well. I am now launched on, at least, a two-year

study of the Charles Bargue drawing course.

Here is a drawing produced according to Freitas recommendations, applied to a Bargue plate from the Charles Bargue Drawing Course by Gerald M. Ackerman. This post is mostly for my own study, although I hope is will be of some interest to those who enjoy the study of art, and that it might also serve as an example of how determined effort can produce some level of success in all aspects of life.

Plate I, 27. Leg of Germanicus, front view:

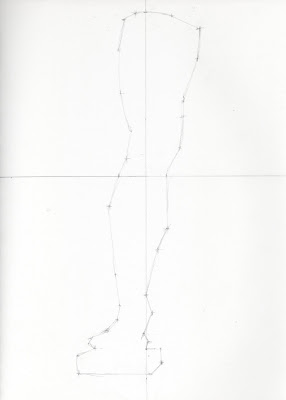

Copying the Schema

I divided the plate into the schema and the finished model, enlarging them via my photo shop program to fill an 8 ½ X 11 inch sheet of paper, and started the process.

Tape down the image in a vertical placement; use a T square or measure equal distance from ends of the board to establish a vertical line, and then line up the paper on this “plumb line”.

Construction – block in the Bargue schema, the construction outline. Make sure the outline contains sound structures of the object to be blocked in. Start with large proportions, widths and heights indicated by points.

Frame the vertical plumb line to get distance to right and left and use the horizontal plumb lines to mark high points top to bottom.

Mark “high points” with a tiny cross (+) with the high point established at the center. Measure how tall and how wide; strive for perfection – to see as accurately as possible.

Construction – block in the Bargue schema, the construction outline. Make sure the outline contains sound structures of the object to be blocked in. Start with large proportions, widths and heights indicated by points.

Frame the vertical plumb line to get distance to right and left and use the horizontal plumb lines to mark high points top to bottom.

Mark “high points” with a tiny cross (+) with the high point established at the center. Measure how tall and how wide; strive for perfection – to see as accurately as possible.

Once the schematic of the horizontal and vertical is set up – actually measure the “widths” of the parts of the drawing. Example: 1) full width – many times in many places, 2) full height – in many places, many times.

Use the needle as a moving plumb line, line up the needle on various highpoints and follow down the drawing to see if it matches the “model”. Keep parallel to vertical plumb line on the model and the drawing. Measure the high points on the schema and check them on the drawing. Check

the horizontal relationship as well.

Use the needle as a moving plumb line, line up the needle on various highpoints and follow down the drawing to see if it matches the “model”. Keep parallel to vertical plumb line on the model and the drawing. Measure the high points on the schema and check them on the drawing. Check

the horizontal relationship as well.

Once the dots are connected, closely examine the Bargue schema and carefully copy it.

This will produce a copy of Bargue’s “schema”.

This will produce a copy of Bargue’s “schema”.

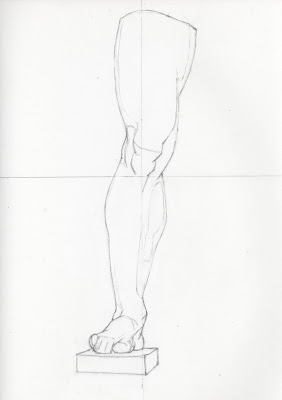

Articulation – separation of light and dark: Place finished (fully rendered) Bargue lithograph

in the exact placement – make vertical and horizontal plumb lines on the backing. To do this overlay to trace center and horizontal plumb lines onto the copy of the fully rendered Bargue lithograph.

Measuring contours: Layer info on top – erase underneath. Find edges of shadow. Also – outline

overlapping forms. Map out details of contour and of shadow edges.

Massing in: Divide light and dark with line, then color in up to the edges. Make it uniform – highest contrast of light and dark, (light and dark families). Use soft pencil to fill in shadow shapes – to discover character of shape – as accurately as possible. Go up to the edge of uniform value.

As one Masses in shapes try to see them as some “abstract” or literal shape – such as a dogs head or a snarling wolf, an egg, bull’s horns, or a bear. Check one shape at a time – both positive and negative shapes. Use a mental image of a clock to gage positions. One should flip one’s eyes back and forth to check for differences. Make adjustments with either the pencil or the eraser. Tap the eraser gently to lift off dark marks.

At this point, A two tone drawing has been produced, the white o the paper and a single, flat, standard tone to represent the dark.

Freitas recommends tracing a copy of the “cheep white paper” drawing onto a sheet of Stonehenge paper for producing the final drawing. For the drawing I am showing here, I do not do this. Rather, I go on to follow his “modeling” and “rendering” instructions

directly on top of the “silhouette” shown above.

For this drawing, I have continued to work on the “cheep white” paper. At present my study

entails doing the selected Bargue copies in a wire bound Strathmore sketch pad. So I applied the finish work directly to the “silhouette” which Freitas calls the “carton”.

Freitas recommends tracing a copy of the “cheep white paper” drawing onto a sheet of Stonehenge paper for producing the final drawing. For the drawing I am showing here, I do not do this. Rather, I go on to follow his “modeling” and “rendering” instructions

directly on top of the “silhouette” shown above.

For this drawing, I have continued to work on the “cheep white” paper. At present my study

entails doing the selected Bargue copies in a wire bound Strathmore sketch pad. So I applied the finish work directly to the “silhouette” which Freitas calls the “carton”.

A. Massing in the Shadows. (*These steps were already done in the production of the “cartoon”.)

1. Start by shading around the contours of the shadow shapes. Make sure the pencil is sharp! Use a 2B.

2. Proceed to shade in the interior of the shadow pattern.

3. In the first “lay in”, make the tone as uniform as possible.

* The tonal value should be the predominant value that permeates the shadow. (1 – 9)

4. The second pass at “laying in” continues to perfect the overall uniformity of the value by filling in gaps in the tone.

* Remember, you are only after the one dominate value, do not attempt light or dark tones in the shadow during this stage.

5. In your third, final pass at filling in the shadow, move over to a harder pencil to fill in even tighter, making the tone even and the shape flat.

6. Use the soft kneaded eraser to lift any dark specks from the shape.

a. The pressure that is applied to the eraser can bemodified to lift either more or less graphite.

1. Start by shading around the contours of the shadow shapes. Make sure the pencil is sharp! Use a 2B.

2. Proceed to shade in the interior of the shadow pattern.

3. In the first “lay in”, make the tone as uniform as possible.

* The tonal value should be the predominant value that permeates the shadow. (1 – 9)

4. The second pass at “laying in” continues to perfect the overall uniformity of the value by filling in gaps in the tone.

* Remember, you are only after the one dominate value, do not attempt light or dark tones in the shadow during this stage.

5. In your third, final pass at filling in the shadow, move over to a harder pencil to fill in even tighter, making the tone even and the shape flat.

6. Use the soft kneaded eraser to lift any dark specks from the shape.

a. The pressure that is applied to the eraser can bemodified to lift either more or less graphite.

b.The eraser is a very flexible drawing tool. It can be shaped as a wedge to shape and

clean edges.

* To insure one can erase all marks cleanly, DO NOT press hard in the making of outlines.

7. Light pressure is applied to the pencil as it fills voids in the tone.

8. Establish unique abstract, light and dark shapes. Flip eyes back and forth to see differences

in these “abstract” shapes.

B. Modeling the Darks

Once shapes are in place and the dominate value has been applied, begin to work values inside the shadows to model the darks = rendering the darks.

What is inside the shadows?

Reflected light

Darkening along the edge of the shadow.

Contained shadow.

Cast shadow.

Edges – between tonal values

Hard

Soft

Blended

Lost

These have shapes produced by tones and the blending between tones.

D. Rendering the Shadows

1. Using a 2B, begin to establish the darker values in the shadow.

a. Begin to establish the harder edges on the shape.

b. Using the kneaded eraser, clean the edges.

c. Blend the darkness into the interior shadow.

d. Soften the bed bug line and establish a slightly darker value.

e. As you are establishing the range of values, continue to perfect the shape.

f. Using a sharp tip on the kneaded eraser, gently tap out tone to establish the lighter values in the shadow.

g. Keep pushing and pulling the value until they sit correctly.

2. Cast Shadows within a shadow:

a. Using a 2B, begin to establish the darker values in the shadow.

b. Begin to establish the harder edges on the shape.

(1). By establishing the darkest dark, we are separating the

cast shadow from the contained shadow.

(2). Soften the bed bug line and establish a slightly darker value.

clean edges.

* To insure one can erase all marks cleanly, DO NOT press hard in the making of outlines.

7. Light pressure is applied to the pencil as it fills voids in the tone.

8. Establish unique abstract, light and dark shapes. Flip eyes back and forth to see differences

in these “abstract” shapes.

B. Modeling the Darks

Once shapes are in place and the dominate value has been applied, begin to work values inside the shadows to model the darks = rendering the darks.

What is inside the shadows?

Reflected light

Darkening along the edge of the shadow.

Contained shadow.

Cast shadow.

Edges – between tonal values

Hard

Soft

Blended

Lost

These have shapes produced by tones and the blending between tones.

D. Rendering the Shadows

1. Using a 2B, begin to establish the darker values in the shadow.

a. Begin to establish the harder edges on the shape.

b. Using the kneaded eraser, clean the edges.

c. Blend the darkness into the interior shadow.

d. Soften the bed bug line and establish a slightly darker value.

e. As you are establishing the range of values, continue to perfect the shape.

f. Using a sharp tip on the kneaded eraser, gently tap out tone to establish the lighter values in the shadow.

g. Keep pushing and pulling the value until they sit correctly.

2. Cast Shadows within a shadow:

a. Using a 2B, begin to establish the darker values in the shadow.

b. Begin to establish the harder edges on the shape.

(1). By establishing the darkest dark, we are separating the

cast shadow from the contained shadow.

(2). Soften the bed bug line and establish a slightly darker value.

The Light - Rendering the Lights

Half tones help create the illusion of the three dimensionality of the form. They allow the artist to wrap the form. They follow the surface of the form and help us know how much it turns, (how full, round, or blocky) the form is. The geometric forms – cube, cone, cylinder, and sphere – are all found on the surface of the face and figure.

The longer the

transition the shallower the form; the quicker the change in value the quicker the form will turn. Start at the inside of the value and grow out to shape it. Mainly use HB and 2H pencils for lighter tonal values. The darker pencil will overstate the tonal value. Also, work with the eraser.

Modeling the Lights

See the forms to be modeled. Search the entire form and isolate the shapes of shading.

1. Begin to shape the form. Be aware of the spaces of light between the sections of any shadow.

2. Establish darker half tones to suggest the form.

3. Using the pencil’s point, soften the values into each other.

4. Be aware of how the values of the form turn from darks to lights.

Rendering the Lights

1. Values to be considered on the “light side” are lighter, mid tone, and darker half tones.

2. Look at areas of value: how dark, how light, how the edges blend. *Note – the lightest area

is often just under the shadow area or somewhere to the center of a sphere.

Half tones help create the illusion of the three dimensionality of the form. They allow the artist to wrap the form. They follow the surface of the form and help us know how much it turns, (how full, round, or blocky) the form is. The geometric forms – cube, cone, cylinder, and sphere – are all found on the surface of the face and figure.

The longer the

transition the shallower the form; the quicker the change in value the quicker the form will turn. Start at the inside of the value and grow out to shape it. Mainly use HB and 2H pencils for lighter tonal values. The darker pencil will overstate the tonal value. Also, work with the eraser.

Modeling the Lights

See the forms to be modeled. Search the entire form and isolate the shapes of shading.

1. Begin to shape the form. Be aware of the spaces of light between the sections of any shadow.

2. Establish darker half tones to suggest the form.

3. Using the pencil’s point, soften the values into each other.

4. Be aware of how the values of the form turn from darks to lights.

Rendering the Lights

1. Values to be considered on the “light side” are lighter, mid tone, and darker half tones.

2. Look at areas of value: how dark, how light, how the edges blend. *Note – the lightest area

is often just under the shadow area or somewhere to the center of a sphere.

3. Consider the direction of light: Value moves from light to dark, or from dark to light; turning the form equals the turning of the light. Half tones change in relation to the change of direction in the form.

A. Modeling the Lights

See the forms to be modeled. Search the entire form and isolate the shapes of shading.

1. Begin to shape the form. Be aware of the spaces of light between the sections of any shadow.

2. Establish darker half tones to suggest the form.

3. Using the pencil’s point, soften the values into each other.

4. Be aware of how the values of the form turn from darks to lights.

B. Rendering the Lights

1. Values to be considered on the “light side” are lighter, mid tone, and darker half tones.

2. Look at areas of value: how dark, how light, how the edges blend. *Note – the lightest area

is often just under the shadow area or somewhere to the center of a sphere.

3. Consider the direction of light: Value moves from light to dark, or from dark to light; turning the form equals the turning of the light. Half tones change in relation to the change of direction in the form.

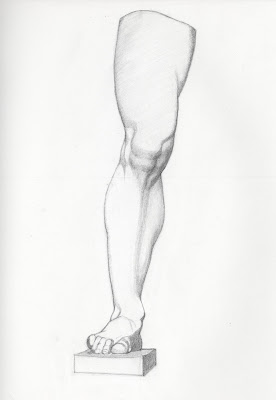

Finishing the Drawing

After dealing with all of the dark “family” and all of the “light” family, going around piecemeal and dealing with all values in both families, one has produced an illusion of a three dimensional form. It has a sculptural appearance and looks finished.

However, having dealt piece meal one has lost sight of the “big picture”. So step back and review

all areas and see if there has been a loss of contrast. In other words, are some values too close

together or too soft? Consider punching the darkest darks; examine the hard edges. Is there a need to lighten the highlights with the eraser?

This tweaking will give the drawing punch and oomph!

First comes “line work”. Look at how thick or thin the lines on the model (the Bargue lithographs) are and make sure they are faithfully reproduced on the drawing. Examine the edges of the contours of the main form and of all inner forms.

Check value relationships between lines; some will be light, some mid-tone, some very dark.

Second, accenting and highlighting. Carve hard dark lines with the 2B pencil. Also, form a “chiseled eraser” and clean any fussiness or softness next to the darkest darks and the lines that form their edges next to the “paper”, which is the lightest value. *Don’t change the shape of the drawing. Razored edges will pop forms off the background.

Go all around the contours and check the lines for thickness, value, and length. Some will be thin, some thick, some short, some medium, some long.

This produces the finished drawing.

A. Modeling the Lights

See the forms to be modeled. Search the entire form and isolate the shapes of shading.

1. Begin to shape the form. Be aware of the spaces of light between the sections of any shadow.

2. Establish darker half tones to suggest the form.

3. Using the pencil’s point, soften the values into each other.

4. Be aware of how the values of the form turn from darks to lights.

B. Rendering the Lights

1. Values to be considered on the “light side” are lighter, mid tone, and darker half tones.

2. Look at areas of value: how dark, how light, how the edges blend. *Note – the lightest area

is often just under the shadow area or somewhere to the center of a sphere.

3. Consider the direction of light: Value moves from light to dark, or from dark to light; turning the form equals the turning of the light. Half tones change in relation to the change of direction in the form.

Finishing the Drawing

After dealing with all of the dark “family” and all of the “light” family, going around piecemeal and dealing with all values in both families, one has produced an illusion of a three dimensional form. It has a sculptural appearance and looks finished.

However, having dealt piece meal one has lost sight of the “big picture”. So step back and review

all areas and see if there has been a loss of contrast. In other words, are some values too close

together or too soft? Consider punching the darkest darks; examine the hard edges. Is there a need to lighten the highlights with the eraser?

This tweaking will give the drawing punch and oomph!

First comes “line work”. Look at how thick or thin the lines on the model (the Bargue lithographs) are and make sure they are faithfully reproduced on the drawing. Examine the edges of the contours of the main form and of all inner forms.

Check value relationships between lines; some will be light, some mid-tone, some very dark.

Second, accenting and highlighting. Carve hard dark lines with the 2B pencil. Also, form a “chiseled eraser” and clean any fussiness or softness next to the darkest darks and the lines that form their edges next to the “paper”, which is the lightest value. *Don’t change the shape of the drawing. Razored edges will pop forms off the background.

Go all around the contours and check the lines for thickness, value, and length. Some will be thin, some thick, some short, some medium, some long.

This produces the finished drawing.

.

.

.

The Bargue Drawing Companion

Notes on the lectures by Fernando Freitas of the Academy of Realist Art,

Toronto.

The Purpose of this Drawing Course:

Learning How to See

Notes by Delose Conner

Toronto.

The Purpose of this Drawing Course:

Learning How to See

Notes by Delose Conner

The Process –Step by Step

1. Progress form simple to more elaborate Bargue drawings.

2. One needs tools, ability, and skill.

3. Tape down the image in a vertical placement.

4. Use a T square or measure equal distance from ends of the board to establish a vertical line, and then line up the paper on this “plumb line”.

5. Horizontal plumb lines – show anatomical horizontal relationships.

6. Reproduce a “first” copy on “cheep” white paper.

7. Use the knitting needle to extend the horizontal plumb.

8. Work from the center.

9. Start with the 2B – the darkest and safest pencil.

10. Hold the back of pencil to prevent making hard, dark, and hard to remove, ridge cutting marks.

11. Do not scratch along with little marks – Commit – sweep gently back and forth. Make a ghostly mark – very light, although visible to the eye. Hard, dark lines will come later.

*Don’t scratch, don’t press down!

12. Do everything in smooth, human circular motions. Use the pencil as an extension of the wrist, elbow, or shoulder; depending on the size of the arc desired.

13. Straight lines must be drawn in small forced line segments.

Measuring the drawing:

14. Construction – block in the Bargue schema, the construction outline. Make sure the

outline contains sound structures of the object to be blocked in. Start with large proportions, widths and heights indicated by points.

15. Frame the vertical plumb line to get distance to right and left and use the horizontal plumb lines to mark high points top to bottom.

16. Measure the high points.

17. Use the tip of the needle and the thumb and fingernails. Hand positions: Horizontal – thumb on plumb line – tip to end. Vertical – two hand motion, moving the needle up and down.

*The measurements do not need to be 100% perfect – do not use a ruler. A little bit of error

allows one to use the eye to correct the drawing.

18. One must learn to train observation skills by measuring how well one can see (check the work). Measurement and correction strengthens one’s observation of nature. Aim to train an accurate eye that can read value, color, shape, and gesture.

19. Like a weight lifter – slowly build “power” by repetition. After building strength for

a year or two, one can wean off the measurement with the knitting needle.

20. Mark “high points” with a tiny cross (+) with the high point established at the center. Measure how tall and how wide; strive for perfection – to see as accurately as possible.

21. Once the schematic of the horizontal and vertical is set up – actually measure the “widths” of the parts of the drawing. Example: 1) full width – many times in many places. 2) full height – in many places, many times. 3) many pieces, for example, the height of the nose, hair, ear, ect.

(the inner forms of the object).

22. Use the needle as a moving plumb line, line up the needle on various highpoints and follow down the drawing to see if it matches the “model”. Keep parallel to the vertical plumb line on the model and the drawing. Measure the high points on the schema and check them on the drawing.

23. Check the horizontal relationship in the way described for the vertical in 22.

24. Turn the images upside down – this fresh appearance of an abstraction will allow one to see flat shapes. Flip eyes back and forth between the Bargue etching and the drawing.

25. Simple Geometric Shapes:

a) Look at isolated shapes – this uses one’s natural ability and strengthens one’s observation skills. Use the needle to examine – don’t erase errors at once.

b) Mistakes are our friends – they teach us.

26. Articulation – separation of light and dark:

a) Place finished (fully rendered) Bargue lithograph in the exact placement – make

vertical and horizontal plumb lines on the backing.

b) Overlay to trace center and horizontal plumb lines onto the copy of the fully rendered Bargue lithograph.

27. Measuring contours:

a) Layer info on top – erase underneath.

b) Find edges of shadow.

c) Also – outline overlapping forms.

d) Map out details of contour and of shadow edges.

*Check by scrutinizing for accuracy.

28. Massing in:

a) Divide light and dark with line, then color in up to the edges.

b) Make it uniform – highest contrast of light and dark, (light and dark families)

c) Use soft pencil to fill in shadow shapes – to discover character of shape – as accurately as possible.

d) Go up to the edge of uniform value.

*In nature there is no such thing as line – only the edges of shapes; this includes those of light and dark shapes.

** Be as neat and uniform as possible.

29. Mass in the shapes as some “abstract” or literal shape – such as a dogs head or a snarling wolf, an egg, bull’s horns, or a bear.

a) Check one shape at a time – both positive and negative shapes.

b) Use a mental image of a clock to gage positions.

c) One should flip one’s eyes back and forth to check for differences.

d) Make adjustments with either the pencil or the eraser. Tap the eraser gently to lift off dark marks.

AT THIS POINT, A TWO TONE DRAWING HAS BEEN PRODUCED, THE

WHITE OF THE PAPER AND A SINGLE, FLAT, STANDARD TONE TO REPRESENT THE DARK.

30. Transferring the drawing to the “good” paper:

a) Cover the image’s back with 2B graphite. Put on a lot.

b) Place the “smooth” or less toothed side of the Stonehenge

paper facing up.

c) Secure the “cartoon” just at the top so it can be lifted to check if the marks are transferring.

d) Use the HB, the harder pencil, to retrace the outline. Don’t push too hard or it will bruise the paper, but one should push hard enough to leave a mark – be sure to be accurate.

e) Lift the pencil at each change of direction – at each high point – so as not to weaken the drawing.

Rules of Light Logic

I. Lorenzo de Medici’s academy:

A. Drawing cubes, cylinders, and spheres illuminated by a single candle.

B. Chiaroscuro – pictorial representation in terms of light and shade without

regard to color . . . the interplay of light and shadow on or “as if on” a surface.

II. Nature uses light to reveal the geometry of objects in two ways:

1. By the way light falls over the form and changes the amount of light and darkness (know as value) on the different parts of the object.

2. By the hardness and/or softness of the edges of the shadow.

*One can accurately represent these changes by properly using the Rules of Light Logic.

III. The Nine Point Value Scale: Segmenting the scale into nine increments from 100% light at a 1 to 100% dark at a 9.

IV. Light Logic – The examination of the effects of light on a three-dimensional form.

A. The simple/basic forms are spheres, cubes, and cylinders.

B. The artiest reduces all natural forms into these components or parts of them.

V. Two common lighting effects exist in nature:

A. Crest lit – the lighting configuration when the lightest light is found somewhere

within the form. *The light, medium, and dark halftones turn away from the lightest highlight in all directions.

B. Rim-lit is the lighting configuration when the lightest light is found on one side of

the form. *The light, medium, and dark half-tones, from the lightest in one direction, move away from the light, turning into the dark.

VI. Direct light produces the following nine value scale:

1. Bright spot (highlight) – where the light is perpendicular to the surface of the form.

2. Crest or rim light – around the “rim’ of the highlight.

3. Light halftone – local value = normal value of the object.

4. Light medium halftone

5. Medium halftone

6. Dark halftone

7. Reflected light – light reflected from a surface onto the form.

8. Bedbug line – the edge where light and dark sides meet. Where the light

falls off the form = core shadow.

9. Cast shadow – a shadow cast on a surface by a form.

VII. The Silhouette – The division of light and dark (shadow).

The massing in of the dark (shadow/negative) giving the artist a light (positive) is fundamentally the most important statement in representational drawing and painting.

A. The artist achieves a likeness of their subject in a flat statement. This = the “graphic” appearance.

B. The bedbug line (shadow edge, core shadow, or terminator line) is the edge that tells the

artiest when the direct light has fallen off the form.

C. The bedbug line weaves over every surface-change on an object. *The purpose of the bedbug line is to describe the form.

VIII. Contained Shadow:

*Note there are two types of shadow; the form shadow (contained shadow) and the cast shadow.

A. Contained Shadow is the shadow pattern found within the form.

B. The cast shadow is a shadow thrown by the form.

C. All shadows read darkest at their edges.

D. Contained and cast shadows can be broken down into: lighter darks, medium darks, and darkest darks.

1. Lightest darks – value found in the contained shadow and called reflected light.

a. *Reflected light is light that travels past the form and is reflected into the shadow.

b. * How light or dark reflected light is depends on how far the reflected light has traveled: greater = darker / shorter = lighter.

2. The value of the bedbug line will register lighter or darker depending on how “fast” or “slow” the direct light falls off the form.

a. Faster / darker = harder edge of value shape.

b. Slower / lighter = softer edge to the value shape.

Note:

* The squarer or sharper the form the darker and harder the edge.

** The rounder or more blunt, the softer and lighter the edge.

3. The darkness and hardness of the edge is dictated by the planes or facets of the form, and the direction of the light.

IX. Cast Shadow (Thrown Shadow) – Does not have a even value throughout.

A. Harder and darker as the shadows approach the form.

B. Softer and lighter as the shadows move away from the form.

C. The interior of the cast shadow is illuminated by indirect light.

D. Again, the values within the cast shadow will darken closest to the form – getting

lighter away from the form.

E. The Penumbra = partially shaded outer region of cast shadow. It’s length gets longer or shorter as it moves toward or away from the form.

X. The Light = The area of the form illuminated by direct light.

*In “the light” one finds: highest-lights, medium-lights, and dark-lights.

A. Highest light = Highlight

B. Medium-lights and dark-lights are determined by the surface of the form falling

away from the direct light.

1. Change of direction of the facets or planes of the surface causes a change in value.

2. The hardness or softness of the edges of values is determined by how fast the form falls away from the light.

a. The squarer or sharper the planes, the harder the edges.

b. The softer or rounder the planes, the softer the edges.

c. Planes facing the direct light are lighter.

d. Planes turned away from the direct light are darker.

e. Darker half-tones are commonly found closest to the bedbug line.

* Note: In essence, the artist must feel with their eyes how light caresses the

form. This feeling is duplicated in the rendering of the forms.

XI. Rules:

1. The light and dark must be separated – the silhouette (the likeness).

2. The bedbug line must describe the form.

3. The darkest light must be lighter than the lightest dark and the lightest dark must be darker than the darkest light.

4. All shadows must be darker at the edges.

5. Shadow edges on the form must be hard or soft depending on how fast the form curves from

the light. Values along the edge must change – darker if harder edged and lighter if softer edged.

6. Half-tones must wrap or vale the form.

* Bedbug line: “A bedbug walking across the surface of a sphere, steps boldly from the light to the shadow. That’s it.” R. H. Ives Gammell

** “Our tiny bug is either in the light, or he is in the shadow . . . The two worlds are totally

separate and no value occurs in both.” Stapleton Kearns

Materials List

Graphite Pencils: 2B, HB, 2H

Erasers: kneaded and white

Paper: tracing paper, drawing paper, and Stonehenge

paper (light gray or pearl gray)

Drawing Board: 18 X 24 inch plywood or Masonite.

Drawing Tools: utility knife, sand paper block, masking

tape, pencil extenders, 2.25 MM knitting needle, eraser shield, and mall stick

or protection sheet.

The Drawing Process

I. The Dark Side - Massing in the Silhouette

A. Massing in the Shadows.

1. Start by shading around the contours of the shadow shapes. Make sure the pencil is sharp! Use a 2B.

2. Proceed to shade in the interior of the shadow pattern.

3. In the first “lay in”, make the tone as uniform as possible.

* The tonal value should be the predominant value that permeates the shadow. (1 – 9)

4. The second pass at “laying in” continues to perfect the overall uniformity of the value by filling in gaps in the tone.

* Remember, you are only after the one dominate value, do not attempt light or dark tones in the shadow during this stage.

5. In your third, final pass at filling in the shadow, move over to a harder pencil to fill in even tighter, making the tone even and the shape flat.

6. Use the soft kneaded eraser to lift any dark specks from the shape.

a. The pressure that is applied to the eraser can be

modified to lift either more or less graphite.

b. The eraser is a very flexible drawing tool. It can be shaped as a wedge to shape and

clean edges.

* To insure one can erase all marks cleanly, DO NOT press hard in the making of outlines.

7. Light pressure is applied to the pencil as it fills voids in the tone.

8. Establish unique abstract, light and dark shapes. Flip eyes back and forth to see differences

in these “abstract” shapes.

B. Modeling the Darks

Once shapes are in place and the dominate value has been applied, begin to work values inside the shadows to model the darks = rendering the darks.

What is inside the shadows?

Reflected light

Darkening along the edge of the shadow.

Contained shadow.

Cast shadow.

Edges – between tonal values

Hard

Soft

Blended

Lost

These have shapes produced by tones and the blending between tones.

C. Edges

1. Hard edges do not require softening. They remain sharp.

2. Soft edge:

a. Using a tapered eraser point, break up the hardness of the edge by gently taping.

b. Using the point of the pencil, feather the tip across the edge, lifting the point as it enters the lighter area. *This will darken the value along the bed bug line and soften the edge of the shadow simultaneously.

c. Using the point of the pencil gently soften (blend) the bed bug line into the lighter shadow area.

d. Using the hardest pencil, the 2H, soften the transition between the shadow and the light.

3. Blended Edge:

a. Using the tapered point of a kneaded eraser, break up the hardness of the edge, travelling further into the dark tone.

b. Using the HB pencil, travel across the transition, using light long strokes to defuse the edge.

c. Using the HB pencil, use small circular strokes to fill in voids at the appropriate value. *The

circular filling will neaten the transition.

d. Using the 2H, blend the subtle shading.

4. Lost Edge:

a. Using the tapered point of the eraser, break up the hardness of the edge and move even further back into the tone. *The tip of the tapered eraser can be stroked as a pencil to subtly lighten the tone over a broader area.

b. With the HB, use the tip of the pencil to build the tone on the lighter side.

c. Using the tip of the pencil, fill in voids in the darker areas.

D. Rendering the Shadows

1. Using a 2B, begin to establish the darker values in the shadow.

a. Begin to establish the harder edges on the shape.

b. Using the kneaded eraser, clean the edges.

c. Blend the darkness into the interior shadow.

d. Soften the bed bug line and establish a slightly darker value.

e. As you are establishing the range of values, continue to perfect the shape.

f. Using a sharp tip on the kneaded eraser, gently tap out tone to establish the lighter values in the shadow.

g. Keep pushing and pulling the value until they sit correctly.

2. Cast Shadows within a shadow:

a. Using a 2B, begin to establish the darker values in the shadow.

b. Begin to establish the harder edges on the shape.

(1). By establishing the darkest dark, we are separating the cast shadow from the contained shadow.

(2). Soften the bed bug line and establish a slightly darker value.

E. Summery – Massing in the silhouette – rendering the shadows, reviewing the shadow pattern.

Examine the completed rendering – observe light, dark, and medium shadow range – work with 6 – 7 – 8 – 9.

Use 2B and HB pencils to achieve the values in the darker range.

*Note – As a beginner – do only darks first, then the lights. Later one may choose to work on dark and light at the same time.

1. Copy the plate from the Bargue book as exactly as possible.

*To familiarize: Observe the contained shadow, the shadow that actually exists on the form and cast shadows that move off the form to the background. These two fuse together to form one large shadow pattern.

* Cast shadows get harder and darker as they get closer to the source. They get softer and lighter

as they pull away from the source.

* In the contained shadow, there is a lighter (whiter) reflected light close to the supporting form.

* Bed bug line is away from the light of the form – softened depending on how quickly the form is turning.

2. Rendering: Blending shadows so one cannot tell where one value ends and another begins.

Hints:

1. Keep the pencil as sharp as possible.

2. Keep looking at the model – to copy exactly the value shapes – copy the character of the edges.

3. Keep working with the eraser.

4. Work as uniformly and as neatly as possible.

5. Repetition is the way to master these skills sets.

6. It is OK to be continually improving – repetition improves technique.

II. The Light - Rendering the Lights

1. Half tones help create the illusion of the three dimensionality of the form. They allow the artist to wrap the form. They follow the surface of the form and help us know how much it turns, (how full, round, or blocky) the form is. The geometric forms – cube, cone, cylinder, and sphere – are all found on the surface of the face and figure.

2. The longer the transition the shallower the form; the quicker the change in value the quicker

the form will turn.

Notes:

*The most important thing is the illusion of three dimensionality.

** When placing the tonal values in the “light” never outline.

*** Half tones don’t have an outline – they have an edge, some are softer than others.

3. Start at the inside of the value and grow out to shape it.

4. Mainly use HB and 2H pencils for lighter tonal values. The darker pencil will overstate the tonal value.

5. Also, work with the eraser.

A. Modeling the Lights

See the forms to be modeled. Search the entire form and isolate the shapes of shading.

1. Begin to shape the form. Be aware of the spaces of light between the sections of any shadow.

2. Establish darker half tones to suggest the form.

3. Using the pencil’s point, soften the values into each other.

4. Be aware of how the values of the form turn from darks to lights.

B. Rendering the Lights

1. Values to be considered on the “light side” are lighter, mid tone, and darker half tones.

2. Look at areas of value: how dark, how light, how the edges blend. *Note – the lightest area

is often just under the shadow area or somewhere to the center of a sphere.

3. Consider the direction of light: Value moves from light to dark, or from dark to light; turning the form equals the turning of the light. Half tones change in relation to the change of direction in the form.

Notes:

* Directions on the picture plane follow those on a map: north, south, east, west.

** Edges of half tones can be soft and defused – even lost.

*** Lightest tone = the paper.

**** As the form turns away, it gets darker.

C. Summery:

1. Observe all half tones in the light side.

2. Never outline.

3. Start rendering the forms from their center.

4. Use HB and 2H pencils.

Accenting and Highlighting – Finishing the Drawing

I. The general review and accenting of the drawing.

After dealing with all of the dark “family” and all of the “light” family, going around piecemeal and dealing with all values in both families, one has produced an illusion of a three dimensional form. It has a sculptural appearance and looks finished.

However, having dealt piece meal one has lost sight of the “big picture”. So step back and review

all areas and see if there has been a loss of contrast. In other words, are some values too close

together or too soft? Consider punching the darkest darks; examine the hard edges.

Is there a need to lighten the highlights with the eraser?

This tweaking will give the drawing punch and oomph!

II. Line work

Look at how thick or thin the lines on the model (the Bargue lithographs) are and make sure they are faithfully reproduced on the drawing. Examine the edges of the contours of the main form and of all inner forms.

Check value relationships between lines; some will be light, some mid-tone, some very dark.

III. Accenting and Highlighting

Carve hard dark lines with the 2B pencil.

Form a “chiseled eraser” and clean any fussiness or softness next to the darkest darks and the lines that form their edges next to the “paper”, which is the lightest value.

*Don’t change the shape of the drawing.

Razored edges will pop forms off the background.

Go all around the contours and check the lines for thickness, value, and length. Some will

be thin, some thick, some short, some medium, some long.

Summary

What is one trying to learn?

1. Learn to see. Drawing is seeing”!

a) Try to master simple geometric shapes; seeing them and drawing them.

b) Learn to see flat shapes. *master this

c) The eye must become more accurate.

d) Look for the iconic shapes of the light or dark patterns.

Ask – what do these shapes look like? How accurate are their size, proportion, and location? Check the accuracy of the different angles that appear in the shape. (angles – short, long, medium, more vertical or more horizontal)

e) Learn to see the light and dark side – keep the two families separate. Learn values

and value relationships, nine values – from white paper to pure black.

2. Learn to read the values. On the dark side: a) lightest b) medium c) darkest dark.

a) Edges are darker than the interior.

b) Cast shadows move from harder, darker edges closest to the source and move away to lighter or softer shadows.

c) Shadow edge is the bedbug line. Softness of the edge depends on how round or square the form is at the bedbug line. The rounder the form is the softer and lighter

the value of the edge is. Square edges are harder and darker.

3. Learn to look into the value of the lights: lightest light, med-tone light, and darkest light.

*Remember – The lightest dark cannot be lighter than the darkest light, the darkest light cannot be darker than the lightest dark.

4. Lean to see and reproduce the EDGES: hard, soft, blended, or lost.

5. The goal is a representational three-dimensional drawing.

6. Copy the Bargue etchings over and over again to reach a high standard in all skill sets.